Overview

When preparing students for a classroom debate, present the class with a wide variety of relevant sources. After giving students time to move around the room examining the sources, invite different teams not only to nominate sources they wish to “deploy” in the debate to support their case, but also other sources they wish to “destroy” because they might otherwise undermine it. These “destroyed” sources can then be used in different ways later on in the study.

Case Study: The Origins of World War One

Background to the debate

At the end of a detailed investigation of the causes of World War One, focusing largely on the main themes (alliance system, colonial rivalry, arms race, nationalism and imperialism…) I always conclude by getting students to debate “who” rather than “what” was responsible in the form of a courtroom trial. First of all, each member of the class is given a number between one and six – corresponding to Russia, France, Germany, Serbia, Britain and Austro-Hungary – and challenged to produce two prosecution questions blaming that country for World War One (“Is it not true that…which is demonstrated by the fact that…?”). They then get into their teams to compare the questions and decide overall upon their best two. Next, each team is told which country they will be defending (i.e. the country which followed them in the original list, with the team prosecuting the Austro-Hungarians at the end of the list now defending the Russians at the start of it). At this stage, everyone should now be clear who they are prosecuting and who they are defending. Each team is finally given the prosecution questions they will need to answer, and use the remaining time, plus homework as necessary, to frame their responses.

Destroy or Deploy?

In the following lesson, I decided that I wanted students to integrate some fresh primary sources rather than simply rely on their existing classroom notes. This would hopefully get them thinking about the issues from a fresh angle, keep the rest of the class interested during the debate by presenting them with genuinely novel perspectives, and help bring in some evaluation skills as the reliability and utility of the sources was interrogated. So prior to the lesson I printed off a wide range of visual and written sources from past examination papers relating to the origins of World War One. I cut them out and spread these all around the room. When the class entered, they were then given the following instructions:

Surprise witnesses: DESTROY or DEPLOY?

- You will be given 10 minutes to examine the numbered sources around the room.

- As you examine the sources, try to decide:

Which sources support your defence case?

Which source supports your prosecution case?

Which source undermines your defence case?

Which source undermines your prosecution case?- When the 10 minutes are up, each team will take it in terms to to nominate one source to “Destroy” or “Deploy”:

- DEPLOY means you want to use it in the debate: in other words, it helps support the points made by your prosecution questions, or your defence responses.

- DESTROY means you want to remove it from the debate altogether: in other words, it supports your opponents or undermines your defence case.

- The process will be repeated until all groups have made all the choices they wish.

As outlined above, The main part of the process involves teams taking it turn to announce which (numbered) source they wish to “Deploy” (at which point they should be handed their chosen source to keep safe) or to “Destroy” (such sources should ostentatiously be placed into a brown envelope marked “Top Secret” or similar). Expect some howls of protest from groups who were desperately keen to “Deploy” these as part of their own case!

Thereafter, each team should develop their prosecution questions and defence responses as appropriate with the sources they have identified.

Taking it further: What to do with the ‘destroyed’ sources?

The key thing to decide is what use to make of the “destroyed” sources. After all, these are likely to be some of the most interesting and compelling witnesses in the entire debate. There are several options:

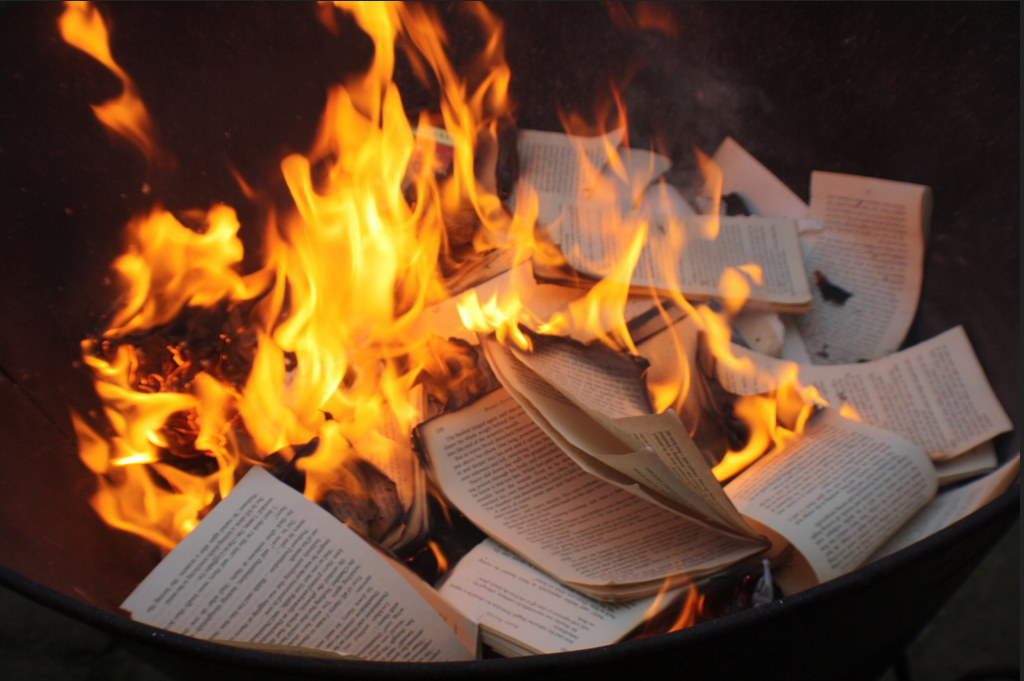

- Tear them into little pieces and throw them away in front of the class. Brutal, but suitably dramatic and might be useful for making a point about gaps in the historical record being something that historians continually have to grapple with.

- Provide them to a series of ‘judges’ in the class (e.g. absentees from the first lesson) to consider and frame their own questions based upon to give them an active role during the debate.

- Use them to produce an examination-style source work exercise so that students are once again presented with a fresh layer of knowledge and interpretation.

- Present them to the class after everyone has had chance to express their final judgement (in this case, using piechart prioritisation) and then ask if, and to what extent, these sources change the class judgement and why.

- Use them as the basis for a display (“CENSORED! The hidden story behind the outbreak of World War One!”) whereby each team has to provide an explanation about why they ‘destroyed’ the sources on display.